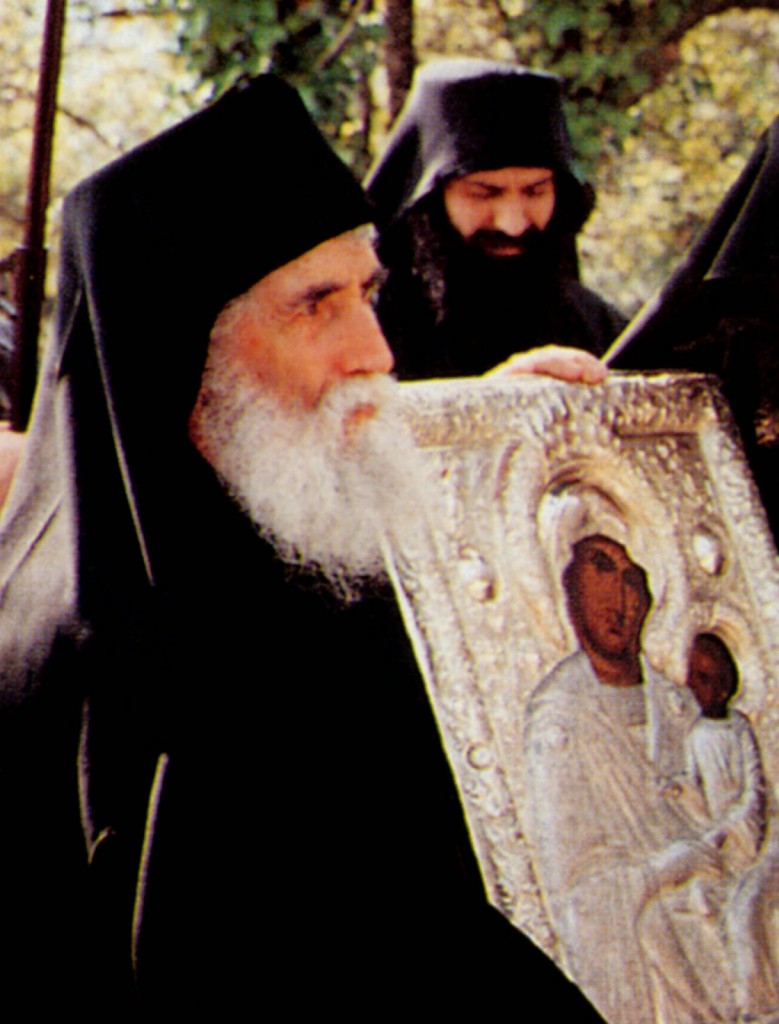

As I mentioned in the recent article about the Elder, I was fortunate enough to translate his biography of Saint Arsenios. As a result of this, I met him on a number of occasions.

Were I a more saintly person, I would no doubt have recognized more easily the sanctity within the Elder, but being a mere word-bodger and erstwhile teacher I noticed things which I had been trained to look for.

The most obvious of these was his intelligence. He really was very bright. With very little formal education, he was still able to read the difficult Greek of the Fathers and quote it as required. When I’d finished the translation, I was asked to write an introduction and did so. What happened then took me back to tutorials in my undergraduate days at Oxford. The Elder said he appreciated the effort I’d put into it and it was very good in its own way, but not really what was required. He went on to suggest a better format, I submitted it and this time it was approved.

He was very perceptive when it came to language. When I translated the Dismissal Hymn for the saint, the question arose as to why I had used ‘you’ instead of ‘thou’. I gave what I thought was a balanced answer: that ‘thou’ is no longer used as an intimate pronoun, but is felt to lend a certain elevation to the text, particularly if coupled with ‘O’ as a vocative. The Elder understood the difference and decided on ‘you’ because it conveys greater familiarity- as I remember, the matter of how one would normally address one’s parents and friends came into the discussion.

His prose style was lively and, on occasion, somewhat earthy. There was no arch sensitivity in his writing: if he meant ‘spade’ he called it a spade. This extended to speaking as well. On one occasion he was getting off the boat at Ouranoupolis with a young monk, and the latter expressed his shock at the state of undress of some of the female tourists. The Elder told him: ‘God made them like that so they can suckle their children. If it bothers you, that’s your problem’. And, of course, given his linguistic gifts and his sense of humour, he enjoyed playing with words. One of his best known examples is that ‘the canons of the Church shouldn’t be used to fire upon the faithful’. His sense of humour is, in fact, one of his best-documented features. On coming round after major surgery, he looked down at the metal discs attached to his chest and said ‘I see I’ve been decorated’.

He expressed regret that he had acquired a ‘name’ and said that doing so was one of a monk’s worst problems. Unfortunately, as his reputation grew he was often quoted out of context in the most surprising of ways. I remember being told by one lady that Elder Païsios had written in one of his books that he was against dish-washers. This seemed unlikely so I checked the reference and what he actually wrote was that back in his home village, people drank out of large cups which were easy to clean, and that nowadays, some people used glasses that were so long and fragile that the only way to clean them was to buy a dish-washer.

But the most vivid of my memories of him was one time when I went to see him at Souroti with my young son in tow. The Elder and my son quite happily sat together on a sofa playing motor-cars, while I was left to contemplate the mysteries of the universe.

May his prayers be with us!